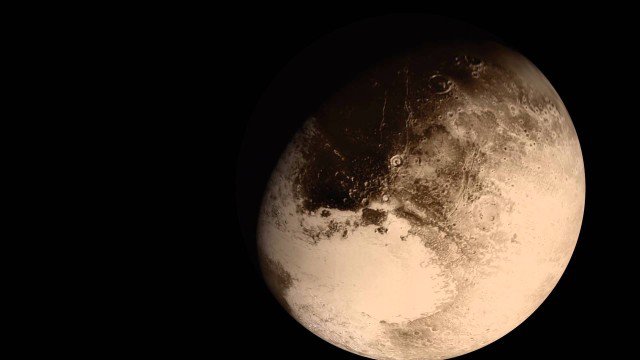

NASA preps up for receiving data from New Horizons’ Pluto flyby

There is a treasure of data and information about the dwarf planet and its moons with New horizons’ after its Pluto flyby. The data is taking time to get back to Earth due to the distance between Earth and Pluto, which is over 3 billion mi or 4.8 billion km. In order to fasten the process, NASA has begun an intensive download from the unmanned spacecraft that will return tens of gigabits of data over the next 12 months.

It’s been seven weeks since New Horizons’ historic flyby of the Pluto system, and during this quick pass, the spacecraft was designed, “To gather as much information as it could, as quickly as it could, as it sped past Pluto and its family of moons – then store its wealth of data to its digital recorders for later transmission to Earth,” said the mission team.

Part of the reason for the delay between the gathering of and transmission of data is because all of the New Horizons instrumentation is body-mounted. In order for the cameras to record data, the entire probe must turn, and the one-degree-wide beam of the high-gain antenna will almost certainly not be pointing toward Earth. Previous spacecraft, such as the Voyager program probes, had a rotatable instrumentation platform (a “scan platform”) that could take measurements from virtually any angle without losing radio contact with Earth. New Horizons ’ elimination of excess mechanisms was implemented to save weight, shorten the schedule, and improve reliability during its 15-year lifetime.

NASA is making the images from New Horizon’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager LORRI available to the public as they come in. The first release is scheduled for September 11. The Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) is a long-focal-length imager designed for high resolution and responsivity at visible wavelengths.

NASA switched on the metaphorical switch on September 5 when an “intensive” downlink session started. Until then New Horizons was concentrating on lower data-rate information from its energetic particle, solar wind, and space dust instruments with only a smattering of images thrown in as insurance against systems failures. The probe is now sending loads of information at a comparatively high rate as it starts a download of high-resolution images and other data that will take about a year.

The first images of Pluto from New Horizons were acquired September 21–24, 2006, during a test of the LORRI. They were released on November 28, 2006. The images, taken from a distance of approximately 4,200,000,000 km confirmed the spacecraft’s ability to track distant targets, critical for maneuvering toward Pluto and other Kuiper belt objects.

New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, “This is what we came for – these images, spectra, and other data types that are going to help us understand the origin and the evolution of the Pluto system for the first time.”

The data that has come in is not even five per cent of what is still aboard New Horizons.

During the Jupiter flyby in February 2007, New Horizons data return rate was about 38 kilobits per second (kbps), which is slightly slower than the transmission speed for most computer modems. Now, after the flyby, the average downlink rate is going to be approximately 1-4 kilobits per second, depending on how the data is sent and which Deep Space Network antenna is receiving it.